Predator on the Reservation

Season 2019 Episode 2 | 54m 48sVideo has Closed Captions

An investigation into the failure to stop a pediatrician accused of sexual abuse.

FRONTLINE and The Wall Street Journal investigate the decades-long failure to stop a government doctor accused of sexually abusing Native American boys for years, and examine how he moved from reservation to reservation despite warnings.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Major funding for FRONTLINE is provided by the Ford Foundation. Additional funding...

Predator on the Reservation

Season 2019 Episode 2 | 54m 48sVideo has Closed Captions

FRONTLINE and The Wall Street Journal investigate the decades-long failure to stop a government doctor accused of sexually abusing Native American boys for years, and examine how he moved from reservation to reservation despite warnings.

Problems with Closed Captions? Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch FRONTLINE

FRONTLINE is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

"Who Am I, Then?"

Explore this interactive that tells the stories of over a dozen Korean adoptees as they search for the truth about their origins — a collaboration between FRONTLINE and The Associated Press.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ ♪ >> NARRATOR: Tonight, a special investigation from "Frontline" and "The Wall Street Journal."

>> There were allegations of drug misuse, stealing, sexual abuse, and inappropriate behavior.

>> NARRATOR: Decades of dysfunction inside the federal agency that provides health care to Native Americans.

>> The Indian Health Service, they just seem impervious to improvement, and they could not get it right.

>> Because of the absolute need to fill positions, we don't really get the best of the best.

>> NARRATOR: And the case of a government pediatrician moved from reservation to reservation... >> My concerns was that this man was sexually using children.

>> NARRATOR: ...despite the warnings.

>> There was obviously a lot of people that knew something was going on, and they didn't do anything.

>> NARRATOR: The Indian Health Service and the failure to stop decades of abuse.

>> What kind of cover-up is this?

This involves a lot of people in a lot of high places.

>> NARRATOR: "Predator on the Reservation."

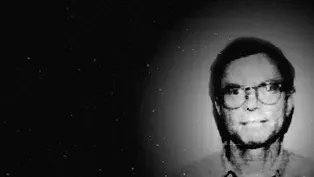

♪ ♪ >> NARRATOR: Dr. Stanley Patrick Weber was a pediatrician working for the Indian Health Service.

>> NARRATOR: His patients were Native American children.

>> NARRATOR: Allegations followed Dr. Weber from reservation to reservation.

♪ ♪ (sirens blaring in distance) (car horns honking) >> NARRATOR: "Wall Street Journal" reporters Christopher Weaver and Dan Frosch have been on the trail of Dr. Stanley Patrick Weber and the government agency he worked for, the Indian Health Service.

>> WEAVER: Starting about two years ago, we got interested in a federal agency called the Indian Health Service.

Their hospitals have had an ugly track record in the last few years.

They were missing diagnoses, patients were dying for no reason.

And we found that the agency had failed for many years to take in hand a series of structural problems that had basically rendered these hospitals incapable of meeting their regulatory requirements.

We found a bunch of doctors with troubled track records before they joined the IHS or once they got there.

In some cases, people who had, who had been convicted of crimes prior to their service with the IHS.

>> And the IHS hired them anyway?

>> WEAVER: The IHS hired them anyway.

>> FROSCH: We began looking into troubled doctors that had got in trouble during the course of their careers at IHS.

And one of those doctors was a guy by the name of Stanley Patrick Weber.

>> WEAVER: Upon finishing the residency, he immediately joined the Indian Health Service.

He was stationed from '86 to '89 at a hospital in Oklahoma, Ada, Oklahoma, that the IHS ran at that time.

He was a pediatrician there.

>> And have we tried to reach him?

>> WEAVER: Yes.

>> And?

>> WEAVER: And he hasn't responded.

>> FROSCH: This doctor being accused of sexual assault by patients.

And we thought that warranted a broader look, both at Dr. Weber, but also at sort of widespread practice of hiring doctors who, who would get into trouble.

>> WEAVER: We thought, "We got to find out, did the IHS know?

"Did anybody have any inkling that there might be an issue with this doctor?"

♪ ♪ >> NARRATOR: In 1992, Dr. Weber arrived in the little town of Browning, Montana, part of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation.

♪ ♪ >> FROSCH: Blackfeet Reservation is about 2,300 square miles.

It butts up against Canada.

This stunningly beautiful place.

Like a lot of Indian reservations, there's high poverty rates, high rates of alcoholism, diabetes, domestic abuse, et cetera.

And so this is really one of the most far-flung places that you could go if you were a doctor.

♪ ♪ >> NARRATOR: The reservation's only hospital was run by the IHS, which struggled to find doctors.

Mary Ellen LaFromboise was the hospital's C.E.O.

at the time.

>> We had been without a, a pediatrician for a while.

So here comes Dr. Weber.

And all I could think of is, "He looks comfortable, huh?"

He looked young.

And just seemed like he was, would be a good fit for us.

>> NARRATOR: One of the first things Dr. Weber did was help expand the hospital's youth outreach programs.

>> They were talking about, "We want to do some things in the school.

"You know, we have some programs that would blend really well with middle school."

I just thought, "Wow, here's something "that the hospital can offer the community.

We'll put Dr. Weber out there in the community."

♪ ♪ >> NARRATOR: Almost from the start, concerns began to emerge.

Tim Davis is the chairman of the Blackfeet tribe.

>> Running Weasel is my Indian name.

>> NARRATOR: But in 1992, he worked in the hospital's facilities department.

>> That green house, 105 is it?

That's the one Weber was in.

>> NARRATOR: Part of his job was to inspect government-owned houses, including the one where Dr. Weber lived alone.

>> So what we did, each annual walk-through, we'd come through each house, and I'd do the inspection of the roof, the floors, the walls, the windows, the doors, and then go through the basement, check out for any leaks.

When I went downstairs was when I was kind of, like, floored, because of what I saw there as a... to me, a signal of something that wasn't right.

The gentleman had a lot of food items, candy, pop, cookies, and then toys, games, videos, games that boys would play with.

I mean, it wasn't just a small, it was stacks of stuff.

I mean, they were stacked.

I mean, I'm a dad, I got boys, I got eight boys, and, I mean, I buy my kids stuff, but it's not stacked up in the basement like, like that was, you know.

And that, to me, signaled there's something wrong with this guy.

>> NARRATOR: Davis says he shared his concerns with Mary Ellen LaFromboise, who at the time didn't see it as cause for alarm.

♪ ♪ ♪ ♪ >> The comments that were coming from maintenance about how there's a lot of traffic of young people in and out of Dr. Weber's, um, quarters.

And I think somebody had asked him about it, why there were so many young people.

"Oh, they, we just like to get together, you know, to have pizza or pop."

You know, things that kids like to do.

He seemed to be genuinely interested in our young people.

He came with the idea of having a, a teen clinic area, you know, by having evening clinics, being more user-friendly to the community.

♪ ♪ >> NARRATOR: Others at the hospital were suspicious of Dr. Weber's intentions.

Psychologist Dan Foster and his wife, Becky, a mental health specialist, knew some of Dr. Weber's patients.

They became increasingly uncomfortable with his after-hours clinic.

>> Normally, if you bring your child to a pediatrician, a parent is with them.

Or if a social worker brings a child to a pediatrician, the social worker is with them, an adult is with them.

But these boys were going in there alone.

♪ ♪ >> It was pre-pubescent, adolescent males.

Most of them teenagers, 12 to 15 years old.

All of them vulnerable, high-risk.

Many of whom we already had suspicions that they'd been sexually molested or, or abused.

And so that, that was a red flag.

And then later, one of our colleagues came and told me he had real concerns regarding this doctor's bringing a couch into his, his office, and that he was keeping young males in there after hours, when most of the staff had gone home.

♪ ♪ >> NARRATOR: While Dr. Weber was on the Blackfeet Reservation, no child is known to have come forward with a specific allegation of abuse.

But Becky Foster remembered one boy who she'd later had concerns about-- Joe Four Horns.

He's now in prison for bank robbery, but spoke to reporter Dan Frosch by phone.

♪ ♪ >> NARRATOR: Joe says he never told anyone at the time what was happening during his visits with Dr. Weber.

But on the reservation, the rumors and suspicions were growing.

>> He took the kids to Great Falls shopping, he took them to basketball tournaments when our kids would qualify.

To us, that was getting the community used to seeing him with these kids and the implication of parental permission.

>> This is grooming behavior.

So you take kids who are high-risk, who are from difficult family circumstances, and who are poor.

And you offer them new clothes, and you offer them food, and you offer them, you know, a home where the lights are on all the time-- a child will gravitate toward that.

♪ ♪ >> NARRATOR: Dan Foster says he decided to confront Dr. Weber.

>> I had these concerns, and I wanted him to know that I was bringing these concerns forward.

My hope was that if he were doing something, he would stop.

And if he weren't, he would be warned and would modify his behavior accordingly.

But, but he did not.

>> FROSCH: How did he respond to you?

>> He was polite, he assured me that he would not harm a child, he was respectful.

And then I just didn't see him after that.

♪ ♪ >> NARRATOR: Finally, after years of suspicion and rumor, there was an incident that couldn't be ignored, involving a boy who'd been sleeping at the doctor's house.

>> There was an incident reported to me where a family member to a kid, you know, went over there and wanted to fight him, and ended up smashing him in, smashing him in the face, breaking his glasses.

Kind of black eye.

I just thought, "You know, he's just going to be, he's going to be a problem."

And then, you know, get with the other staff, and they were, like, "Yeah, you know, something's going on."

♪ ♪ >> NARRATOR: LaFromboise reached out to the region's top IHS official, who summoned the hospital's acting clinical director, Randy Rottenbiller, to his office in Billings.

>> He said, "You know, I'm concerned "that you have a pedophile on your staff, and, and you need to get rid of him."

♪ ♪ And so I just said, "Okay, I've got to deal with this task."

♪ ♪ The first thing I did when I got back to Browning was, called him and asked him to meet me in my office.

And I said, "Well, I've been told that you need to leave."

And he said that he had had some threats made against him, and he was worried about his life, and he was getting ready to leave Browning anyway.

And I think he packed up and left the next day.

I guess the better response would be, launch an investigation.

And, and yet the IHS response is typically to sweep it under the rug, or, you know, or pass it on to some other place.

>> NARRATOR: The IHS would transfer Dr. Weber to its hospital on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

>> WEAVER: The Pine Ridge Indian Reservation is notoriously one of the poorest places in the United States.

The public health situation is dire; life expectancy is among the very lowest in the country.

>> NARRATOR: But within months, a parent was already complaining that Dr. Weber had inappropriately examined a child.

The IHS took him off clinical duties as federal authorities looked into it.

They didn't substantiate the complaint, and Dr. Weber went back to work.

But as in Montana, Weber's interactions with boys continued to raise suspicions.

Kelly Brewer was a nurse who lived across the street from him.

>> The tan house straight ahead, that was Dr. Weber's house.

And then back here was where Dr. Weber's garden used to be.

Like, all this area here, where it's kind of mulched, that was all garden.

He hired kids to work in it all the time, and they were always young Native American boys, ten-ish to 12-ish in age.

>> NARRATOR: The kids coming and going would earn a nickname around the reservation.

>> NARRATOR: One of the so-called Weber boys was named Paul.

Like Joe Four Horns in Montana, he is now in prison, serving time for assault.

(thunder rumbling) (noise buzzing on phone line) >> NARRATOR: Paul says that in exchange for sexual favors, Weber would give him money or prescription drugs.

Like the other boys, he kept his encounters a secret year after year.

>> NARRATOR: One night, he says, he pushed back.

(woman talking on police radio) >> NARRATOR: Tribal police officer Dan Hudspeth was called to the scene.

>> Call came in, there was an assault.

We chased the suspect down, located him not too far from the IHS housing.

We took him into custody, sent him on to juvenile detention.

>> NARRATOR: As Hudspeth took Paul to juvenile detention, he asked him what was going on.

>> NARRATOR: The authorities now had a firsthand allegation of ongoing sexual abuse by Weber.

But on the reservation, the tribal authorities don't have jurisdiction over non-Indians.

So all Officer Hudspeth could do was pass along Paul's allegations to federal investigators.

>> We forward it on to the Bureau of Indian Affairs, criminal investigations, but I'm not quite sure how they ran with it.

All I do know is, personally, I took...

I made sure my, my kids weren't seen anymore by that pediatrician.

>> NARRATOR: The Bureau of Indian Affairs declined to comment, and Paul says no one from the federal government followed up with him.

He kept quiet about what had happened after that.

At the IHS hospital, one of Weber's fellow pediatricians was developing his own concerns.

>> I'd hear him riffing through my charts cherry-picking the, the cute teenage boys.

So at that point, I started having some suspicions about him.

He didn't like seeing babies, didn't like seeing toddlers, didn't like seeing girls, didn't like seeing teenage girls.

So, so just professionally, I just kept butting heads with this guy.

But I couldn't get anybody on the medical staff to listen to me.

>> NARRATOR: In November 2006, Paul did something that made it harder to look the other way.

He wouldn't discuss the details over the prison phone line, but he had one of his friends on the reservation recount what happened.

Henry Red Cloud says he, Paul, and another friend were out drinking and looking for trouble and then ran out of money.

>> All of a sudden, you know, Paul is, like, "You know, man, dog," he was, like, "Let's just go over to (bleep) doctor's house, man, that (bleep) (inaudible), man."

I can't remember if he was (bleep) calling him a child molester or something like that.

I can't remember, but I think I heard something like that.

Paul had it out for Weber.

Maybe it was just because of their little dealings.

And I thought it was (bleep) up, too, 'cause he was my doctor and (bleep).

I knew of several people that used to go and get money from him.

So we went up there, we parked.

As soon as he opened the door, I just kicked the door.

He staggered back, and he dropped, and then I kicked him a few times, hit him a few times, and threw him into the kitchen area.

And then he was fumbling around, and he started walking towards the back into that bathroom, and Dr. Weber was sitting there looking at himself in the mirror.

His eyes were (bleeped) up, bloody mouth, bloody nose.

He was pretty well done for, man.

I said, "You better get that money," so he pulled out a couple hund.

And then he was, like, "Here, here, here, here you go, take it, take it."

He said, "Just don't kill me."

>> NARRATOR: Dr. Weber made his way to the IHS hospital.

Bill Pourier, the hospital's C.E.O., says security guards called him and said one of his doctors had been assaulted.

>> So I went up there.

And Dr. Weber was laying on a, on a gurney in the, in the emergency room.

He looked rather beaten up and traumatized and so forth.

So I asked him, "What's going on here?"

I said, "Who did this to you?"

He wouldn't tell me.

He wouldn't say nothing.

>> WEAVER: He wouldn't say anything at all?

>> He wouldn't say nothing.

And it was frustrating.

>> NARRATOR: Pourier says that he reported what happened to IHS's regional headquarters, but that his bosses never pursued the matter, and he was afraid to take it any further.

>> I probably would have been suspended, maybe even fired.

You know, pretty much, they can do what they want with you.

>> When he was beaten to the point of needing skull X-rays, and no charges were filed for beating up a commissioned officer on federal grounds to the point where he needed skull films, I thought, "What on Earth is going on?

What kind of cover-up is this?"

I mean, this involves a lot of people in a lot of high places.

>> NARRATOR: Outraged, Dr. Butterbrodt would become increasingly fixated on exposing Dr. Weber.

>> I think a lot of people thought I was overreacting.

And people would say to me, "You don't have any real evidence."

And that was always the Indian Health Service line, too.

You know, "We've looked at the data bank, "there's no complaints on him.

He's clean."

And I learned that there was a psychologist who had worked with him at Browning, and was aware of his activities in Browning, Montana, prior to 1995, when he came here.

>> NARRATOR: It was Dan and Becky Foster, who'd had concerns about Weber's behavior on the Blackfeet Reservation.

>> FROSCH: When Mark is telling you guys, basically saying, that crimes have been committed, how did that make you guys feel?

>> Well, I think it...

I think we just...

So you get to be just so angry and frustrated and then just kind of numb.

Because part of what happens is that you can see all of these young people being hurt, and knowing that you've tried to do everything that you could do within the bounds of what's available to you, and then nothing happens.

It says to me as a... Indian woman, as a mother, is that your kids don't matter.

>> I felt deeply hurt and very angry.

The anger was because I felt it was preventable.

>> NARRATOR: In fact, years earlier, Dan Foster had heard Weber was working at Pine Ridge and contacted IHS leaders there to warn them.

>> FROSCH: Would you have said, in as explicit terms, "I'm worried this guy is a pedophile"?

>> Yes.

Oh, I was clear.

My concerns was that this man was sexually using children.

>> NARRATOR: After the encounter, Dr. Butterbrodt was more determined than ever that Weber had to go.

He complained to state medical boards and officials at the IHS.

And he believed he'd finally found proof in a list of patients Weber had ordered tests on.

>> So I looked at these charts, and there weren't any girls.

They were all boys.

On this page, there are 14 patients, and there's one female.

One out of 14.

I kept asking myself, "Why would a pediatrician "zero in on a population consisting of normal-weight boys and teenage boys?"

It just seemed incomprehensible to me.

>> NARRATOR: Dr. Weber was suspended while the allegations were investigated.

>> WEAVER: When Dr. Weber was suspended by the Indian Health Service over allegations of misconduct in 2009, one of the officials who was sent to look into this was this guy Ron Keats.

>> NARRATOR: Keats-- who was one of Weber's superiors at the time-- would soon leave the IHS under a cloud himself, and later be convicted of possession of child pornography.

>> WEAVER: So effectively, they sent a guy who would go on to be arrested a year later of trafficking in child porn to investigate suspicions that their pediatrician could be a pedophile.

>> NARRATOR: Keats did not respond to requests for comment.

Weber was ultimately cleared and went back to work, according to Bill Pourier.

>> The higher-ups, I guess, basically told me there was...

They couldn't find one reason to keep him on suspension.

There was no facts or evidence to support what happened and so forth, and that's pretty much what they gave me, the answer they gave me.

So we just... directed me to put him back to work.

>> WEAVER: At that time, did you believe that Dr. Weber was, you know, potentially engaged in some kind of misconduct towards children?

>> I kind of felt that there could possibly be something going on here, 'cause I started looking at everything.

But I just never got nothing.

I was frustrated, as well.

>> NARRATOR: In the summer of 2010, at the Pine Ridge Hospital, Dr. Weber and Dr. Butterbrodt would clash over the care of a patient.

Dr. Weber claimed he was threatened.

>> Within an hour, I'm sitting in the office of the acting clinical director in Pine Ridge.

And finally, I said something really out of line.

I said, "If I'd wanted to intimidate him, I would have cut his nuts off with a rusty knife."

And that remark went right to Washington.

I was branded as a violent, out-of-control person, and within a few weeks was traveling up to Belcourt, North Dakota, leaving my life and my career and my family, everything.

>> NARRATOR: The IHS sent Dr. Butterbrodt to one of its most remote outposts, 575 miles away, on the Canadian border.

>> The nurses came up to me and said, "Now you know why we don't say anything, Dr. B.

Look what they've done to you."

I was ordered to leave.

I was chased off by a pedophile and the people who chose him over me.

>> NARRATOR: Months later, a new IHS chief medical officer arrived in the region.

>> You, know, it just seemed like the perfect storm of issues that kind of arose.

>> NARRATOR: Rod Cuny determined that Dr. Butterbrodt had been unfairly punished.

>> You know, I credit Mark Butterbrodt, because he, I mean, he laid his career on the line in doing what he needed to do.

Really, he did the right things, and, you know, and he's a direct result of people fearing would happen, what might happen to you.

I mean, it happened to him, and that's why people didn't come forward like he did.

And that's sad that that attitude has to prevail, but, you know, people are scared to come forward.

>> NARRATOR: Many of the officials who ran IHS during the years Dr. Weber was there declined to be interviewed.

But reporter Chris Weaver tracked down Bob McSwain.

>> WEAVER: Mr. McSwain?

>> Yes.

>> WEAVER: Hi, I'm Chris Weaver.

>> NARRATOR: He worked at the IHS for more than 40 years, including two stints as director.

McSwain conceded the agency has long tolerated problem doctors like Weber.

>> It goes back to the, the very heart of, they needed his skills, and so they, they moved him around to, to maintain his, his contribution.

It's fair to say that because of the, the absolute need to fill positions, we don't really get the best of the best.

We get someone who, um...

They have a degree.

(chuckles) They're licensed, and our requirement on licensing is at least licensed in one state in the system.

There's a strange tolerance level, that, "Oh, okay, the guy's a, a womanizer, "or a guy's this, and a guy's that.

But he comes in to see patients," okay?

And the, the antithesis is, "What would it be if he didn't come in?

Who's going to see the patients?"

>> I'm going to call the hearing to order.

This is a hearing of the Indian Affairs Committee.

>> NARRATOR: In 2010, the dysfunction at the IHS got attention in Washington, at the Senate's Indian Affairs Committee.

Senator Byron Dorgan was chairman at the time.

>> We got a couple of employees here that are trouble.

And not only does the employee not get disciplined, but the employee gets a bonus.

We found people who were transferred from one to the other, despite the fact that there were allegations of drug misuse, stealing, sexual abuse, inappropriate behavior, a whole series of things that would, in almost every other circumstance in life, require you to discharge someone, fire someone.

Instead, the Indian Health Service moves them, they transfer them, they move them to the next service unit.

And, "Let's have somebody else live with the, the incompetence and the mistakes."

This system is not working-- this isn't working.

We tried to browbeat the IHS in every way we knew how to get them to straighten out.

And they just seemed impervious to improvement, and they could not get it right.

>> NARRATOR: In the case of Dr. Weber, warnings continued to go unheeded for years.

In 2011, one of them reached Wehnona Stabler, then the C.E.O.

of the Pine Ridge Hospital.

She says a caller complained about Dr. Weber, but didn't provide her any specifics.

The matter never went anywhere.

Stabler later received a gift of $5,000 from Dr. Weber and would plead guilty to not reporting it on a government ethics form.

She didn't respond to requests for comment.

Then, one day in 2015, it all started to unravel.

A tribal prosecutor recalled something Dr. Mark Butterbrodt had told her years before.

>> Mark and I are really good friends.

I've known him since I was in high school, so...

He was frustrated, I remember, one day, and he told me about Dr. Weber and how he was molesting kids.

I was driving to work, and there was snow on the ground when I was thinking about the case.

And I was, like, "I wonder if the attorney general even heard about this."

>> She just asked, "There's some leads that I have on this.

Can I start looking into this and seeing what I can find?"

So I said, "Absolutely.

"If you can find something, let's track it down, and we'll take that information forward."

>> NARRATOR: As in the past, it was hard to get anyone to talk.

>> Weber's alleged victims are all boys.

So, you know, it's even that much harder to get a, a boy or a man to speak about sexual abuse.

So I think trust is a big thing.

>> We felt it was a priority to at least identify a potential victim, so that it wouldn't be dismissed anymore, so that it would be taken seriously, and a full investigation would happen.

>> NARRATOR: They began to look into the assault on Dr. Weber a decade earlier.

>> I learned that he was beat up really bad.

That he was so beaten that he had to get MRIs done.

What I think people should've noticed was that he didn't press any charges on anybody.

>> And those whole circumstances just looked, um, odd.

There was something not right about that.

>> And I did go looking for that police report, 'cause if he was beat up so bad, you know, the ambulances should have came, police officers should've came, but...

I couldn't find anything.

>> NARRATOR: After months of searching, she found a woman who said she knew the boys who'd done it.

>> But she didn't give me much detail.

She just said, "Yeah, they came to me that night after they beat up Dr.

Weber."

She gave me the name of one of them.

And I was, like, "All right, fine, I have this one name to go on."

We found out he was in prison, state prison.

>> NARRATOR: It was Paul.

By then in his late 20s.

>> And after we received that information, we provided that, that potential victim's name to the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

>> NARRATOR: Federal investigators followed the trail the tribal authorities had uncovered.

It started with Paul's name and led to Dr. Weber's door.

>> NARRATOR: The years of accusations had finally caught up with Dr. Weber.

Federal prosecutors would charge him with the abuse of four boys on Pine Ridge and two on the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana.

In September 2018, more than two decades after he was forced off the Blackfeet Reservation, Dr. Weber arrived at the courthouse in Great Falls, Montana, to stand trial.

The first witness was Joe Four Horns.

Now 35 years old.

>> FROSCH: In walks Joe, and he is this muscle-bound guy, tattoos on his face, shackled.

Very tough-looking guy.

The prosecutor, in her opening statement, she puts up a picture of Joe Four Horns when he was about ten or 11 years old, right around the time that he would have been abused by Dr. Weber.

She wants the jury to remember this little boy.

>> NARRATOR: Recording was not allowed in the court; this is the trial testimony voiced by actors.

>> Can I call you Joe?

>> Yeah.

>> FROSCH: Joe answers their questions.

It's clear he does not want to be on the stand.

>> Did he ever kiss you?

>> Yeah.

>> Where did he kiss you?

>> The lips, my face, my neck, and my chest.

>> Did he touch any other part of your body with his hand?

>> Yeah, my penis.

>> FROSCH: Dr. Weber is sitting there, emotionless... >> Did you ever touch his penis?

>> FROSCH: Placid... >> Yeah, yes.

>> Why did you do that?

>> Because he told me to.

>> FROSCH: He looks more like the little boy on the screen than he does the hardened felon that is sitting there.

He's talking about the most humiliating thing that he could ever imagine talking about.

He breaks down crying.

>> NARRATOR: Dr. Weber's attorney questioned why Joe had never spoken up before.

>> FROSCH: Joe reacts in a way that undercuts the defense's entire sort of line of questioning.

>> Right now, I don't want to talk about this.

I don't ever want to talk about that.

>> FROSCH: And explained in really sort of honest, gut-wrenching, visceral terms, why he had never told anybody about this.

>> I got molested as a little kid, man, I don't want to talk about that.

All right, I'll tell you the truth: Those pieces of (bleep), those child molesters, they deserve to be in prison.

They don't deserve to be on the street.

They deserve to get (bleep) (bleep) up and (bleep) killed in prison.

And that's what's going to happen.

>> FROSCH: So during his testimony, and as he began sort of discussing in detail what had happened to him, his mom had to leave the courtroom in tears.

>> NARRATOR: Marion Four Horns had lost custody of her son during those years.

>> I never knew about any of this.

And I feel bad for my boy, because I wasn't able to protect him.

I feel, I really feel... (sobbing) I really hurt for him, I don't know what to do.

(sniffling) >> NARRATOR: The extent of the allegations against Dr. Weber would begin to emerge as the trial unfolded, with more men describing what they said he'd done to them as boys.

>> FROSCH: The prosecution brings several corroborating witnesses from Pine Ridge.

And as was the case with Joe, you see these tough guys sort of reduced to little boys.

>> NARRATOR: Despite the testimony against him, Dr. Weber continued to shrug off the allegations.

>> It's a nice day today.

Nice sunny day.

>> NARRATOR: On the third day of the trial, the jury came back with its verdict: guilty on multiple counts of sexual abuse.

Weber is appealing, and later this year, he's scheduled to go on trial in South Dakota for alleged abuses there.

>> I'm very glad that he was caught.

I still am frustrated that he was allowed to work for so long in that environment.

I think I'm still frustrated that more people haven't been charged criminally.

>> There was obviously a lot of people that knew something was going on.

And they didn't do anything.

(sniffles) They just... let him go.

(sniffles) I feel like somebody should pay for, for what all these boys went through, because people knew.

>> NARRATOR: To date, no one else in the IHS has been held accountable.

And many of the officials who oversaw Dr. Weber did not respond to requests for comment.

But following questions from "Frontline" and "The Wall Street Journal," the agency ordered an independent investigation of Weber's tenure.

The current head of IHS agreed to talk about it and asked to do the interview at the hospital on Pine Ridge where Weber had worked.

>> Hello.

>> NARRATOR: Rear Admiral Michael Weahkee has been leading the agency since 2017.

>> Since this case has came to light, we've been doing a lot of checking internally, to, to see what people may or may not have known.

If there are individuals who were aware that something was going on, then you're basically culpable and complicit in those actions.

I'm in the process now of developing a new policy that will require that every Indian Health Service employee be a mandatory reporter.

>> WEAVER: Of what?

>> Of any potential child abuse, any sexual assaults, any, anything potentially criminal in nature.

>> WEAVER: And what would be a satisfying resolution to the crisis around the case of Dr. Weber?

>> That he do his time.

And that he pay for what he did.

Uh...

He did a lot of damage to our agency.

We've talked a lot about the difficulties we have recruiting providers.

This isn't going to help.

>> WEAVER: Where do you set the bar for yourself, in terms of leading the agency out of this crisis?

>> I think the bar is extremely high.

There are so many people depending upon us.

My own family receives their health care through the Indian Health Service, so I go home every day and... (sniffles) (voice trembling): The expectation is to fix this.

(quietly): Sorry.

>> NARRATOR: In January 2019, Dr. Weber-- now 70 years old-- was sentenced to more than 18 years in prison.

But haunting questions remain.

>> You know, it doesn't sit well that somebody like this monster came in and did what he did.

You know, and I didn't do much to prevent it.

(exhales) I certainly could have done more.

>> Well, at that time, you think of your career and your job and your livelihood, so I probably would have got fired.

I guess that was the risk I would've took.

I couldn't afford to take the risk at that time, to lose my job.

Do I feel responsible for it?

No.

No.

>> I guess I have to blame the bureaucracy of Indian Health Service.

But I have to say, it was on my watch that happened.

I should have known better, but I didn't.

That, that's still hard for me to... kind of deal with.

♪ ♪ >> NARRATOR: After nearly 30 years, no one knows how many victims of Weber's abuse are still out there, or how many other people in the Indian Health Service could have done more to stop him.

♪ ♪ >> Go to pbs.org/frontline and wsj.com for the latest reporting on the story.

And learn more from the reporters about investigating the Indian Health Service.

>> We found a bunch of doctors with troubled track records before they joined the IHS or once they got there.

>> Then, visit our watch page, where you can view more than 200 "Frontline" documentaries.

Connect to the "Frontline" community on Facebook and Twitter, and sign up for our newsletter at pbs.org/frontline.

>> NARRATOR: It was a landmark ruling-- thousands of New Yorkers with severe mental illness had a right to live on their own... >> There was a huge question about whether people that had been institutionalized can live successfully in the community.

>> NARRATOR: ...and a right to fail.

>> They just brought me there and said, "Ta-da!"

>> NARRATOR: "Frontline" and ProPublica investigate.

>> Did it feel like you were left alone?

>> I had no company, actually.

>> The question is, when do you take away somebody's liberty?

>> For more on this and other "Frontline" programs, visit our website at pbs.org/frontline.

♪ ♪ To order "Frontline's" "Predator on the Reservation" on DVD, visit shopPBS, or call 1-800-PLAY-PBS.

This program is also available on Amazon Prime Video.

♪ ♪

"Predator on the Reservation" - Prologue

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S2019 Ep2 | 1m 6s | An investigation into how the government failed to protect children from a pedophile. (1m 6s)

"Predator on the Reservation" - Preview

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S2019 Ep2 | 31s | An investigation into the failure to stop a pediatrician accused of sexual abuse. (31s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Funding for FRONTLINE is provided through the support of PBS viewers and by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. Major funding for FRONTLINE is provided by the Ford Foundation. Additional funding...